Revisiting Canadian Air Power in the Normandy Campaign:

Revisiting Canadian Air Power in the Normandy Campaign: The Geography and Archaeology of 143 Wing Ground Attacks

By David G Passmore and David Capps-Tunwell

This contribution to Project ‘44 explores the locations and target types attacked by 143 Wing RCAF Typhoons between D-Day (6th June) and the culmination of the Normandy Campaign in the final days of August 1944. It builds on Alexander Fitzgerald-Black’s mapping of RCAF airfield locations in Normandy (https://www.project44.ca/intelblog/canadianairpower), and together these approaches are beginning to yield the first systematically documented, day-by-day geographical account of ground attack operations conducted by Allied fighter-bombers over Normandy.

Typhoons ready for takeoff

Our work started as an exercise at ground level following archaeological surveys in several Normandy forests and woodlands – here there are many examples of well-preserved landscapes associated with the German defence of the region including field fortifications, ammunition and fuel depots and the bomb craters of Allied air attacks (Fig. 1). Indeed, bomb craters are likely the most abundant archaeological features of the campaign to survive in the modern landscape, and this has prompted a research programme that is drawing on archives of wartime documents and aerial photographs to identify the aircraft and aircrews associated with specific areas of cratering.

Figure 1: Bomb crater associated with a direct hit on a German 7th Army fuel storage bunker (low rectangular structure) in the Forêt Domaniale des Andaines, Normandy (Photo: DP).

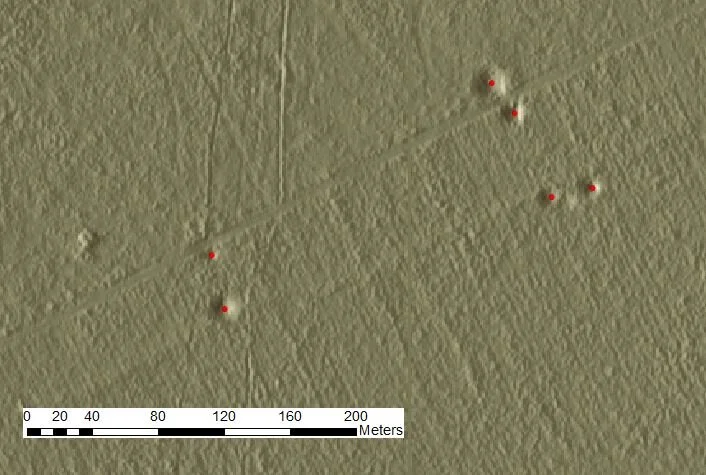

Much of our work to-date has focused on raids by medium bombers of the US Ninth Air Force on supply depots and Seine bridges[1] [2], but we had also noticed in other locations the frequent survival of small clusters of craters or sometimes single or paired examples that may have reflected attacks by fighter-bombers (Fig. 2). Beginning with the three Typhoon squadrons of 143 Wing (438, 439 and 440 Squadrons) we started analysing the Squadron Operational Record Books (ORBs)[3] to locate sites attacked during the Normandy campaign, and especially those targets located in woodlands where there is good potential for archaeological survival. This has led to some early success in finding craters that are likely to be the signature of 143 Wing attacks preserved in the modern landscape (see below). But we quickly grew interested in the broader geography of 143 Wing’s ground attack operations and, with the prospect of integrating this information with the Project ‘44 dataset, we have embarked on a more systematic, day-by-day assessment of RCAF ground attack missions in support of Allied armies in Normandy.

Figure 2: Digital terrain model showing paired bomb craters near a forest road in the Forêt Domaniale de la Londe-Rouvray (Lower Seine valley). These are likely to reflect attacks on German vehicles by fighter-bombers conducting ‘armed reconnaissance’ missions (Data courtesy of Office National des Forêts).

In this first phase of the project, we have completed the analysis of 143 Wing attacks and hope to add equivalent data for the RCAF Spitfires of 126 Wing shortly. Here we provide an outline of the data sources and methodology, and some initial thoughts on how this material can augment the historical record and landscape heritage of RCAF operations over Normandy. General operational details, pilot casualties, and many aspects of Squadron life in 143 Wing over the course of the Normandy campaign have been documented in Hugh Halliday’s (1992) WW2 history of Canadian fighter-bomber pilots.[4] Jack Hilton also offers a veteran’s perspective as a pilot with 438 Squadron.[5]

Typhoons in Normandy

Hawker Typhoon, Vickers-Supermarine Spitfire, Republic Thunderbolt, and North American Mustang aircraft at an Allied mobile repair section, Normandy 25 June 1944

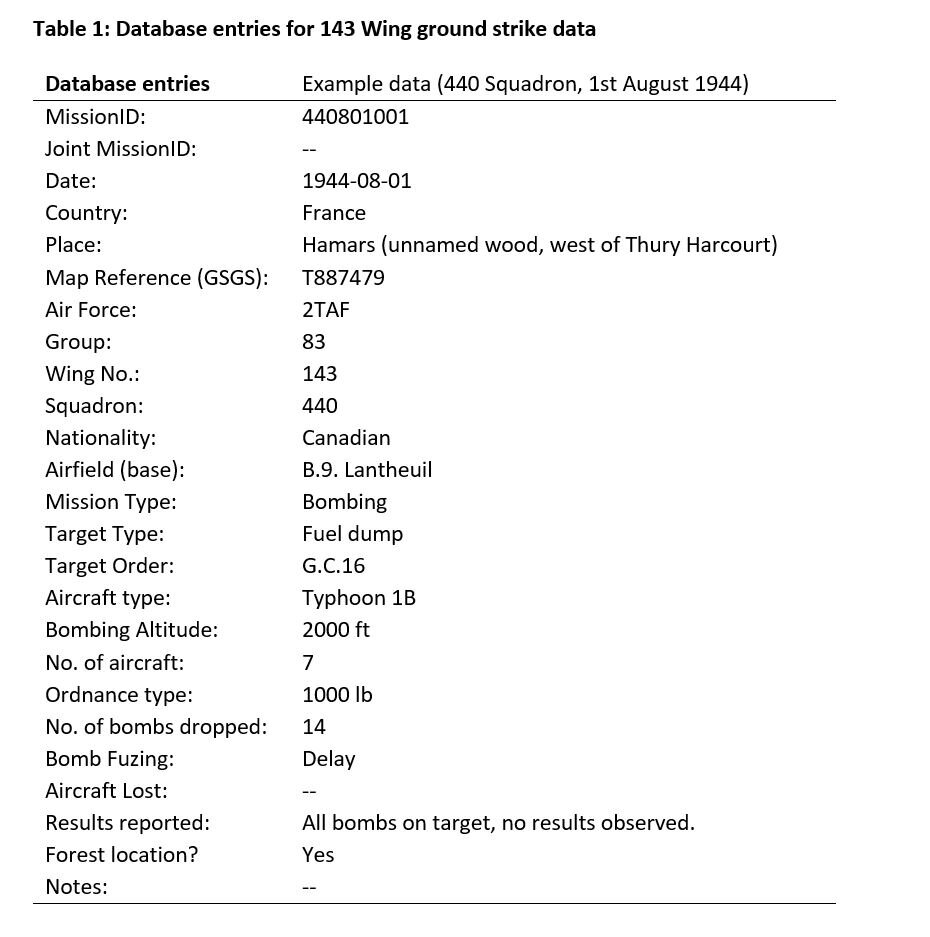

However, as is typically the case with histories of tactical air operations, these do not provide a detailed day-to-day listing of what was attacked and where. Accordingly, in assembling this material for Project ‘44 we have attempted to document the location and details of every ground attack conducted by 143 Wing. Squadron ORBs are the key data source since these provide a daily record of mission types and targets (often including map coordinates and place names), aircraft and pilot lists, and a brief report on the outcome of the mission. An example of an entry for 440 Squadron on the 1st of August can be seen in Fig. 3. These records have been supplemented by 143 Wing ORB’s and especially RAF Second Tactical Air Force Daily Logs.[6] The latter has sometimes proved helpful for confirming or supplementing target details and map references where these are lacking in the Squadron ORB’s.

Figure 3: Mission details for a 440 Squadron operation on the 1st August 1944 (extract from the Squadron ORB).

Each target attacked was assigned a unique ‘MissionID’ record in the database comprising a two-digit number for the year (44), a four-digit number specifying the month and day (xxyy) and a three-digit number assigned on a sequential basis from 001 (this number being reset to 001 for each day). Thus, for example, the raid on 1st August detailed in Fig. 3 was assigned a MissionID of 440801001. For mapping purposes, the database presented here does not include uneventful or non-combat missions, and nor does it include the record of air-to-air combat (although mission entries do note when pilots are lost in action). A full list of database information uploaded to Project ‘44 can be found in Table 1.

These wartime documents have revealed 143 Wing to have conducted 363 ground attack missions between 6th June and 31st August, with a further 24 missions being aborted or seeing no combat (including weather recces, convoy patrols and air-sea rescue flights) (Fig. 4). Only on 20 days were some or all the squadrons grounded by weather or diverted by airfield transitions. Of the completed ground attack missions some 288 (74%) were dive-bombing attacks against pre-arranged or Army-requested targets, especially concentrations of tanks, troops and guns, road bridges and military headquarters and camps. Indeed, apart from seven raids against ‘NoBall’ targets (V-weapon facilities) on 20th June, all 143 Wing bombing missions were directly or indirectly supporting Allied ground forces fighting in Normandy. The Wing also flew 81 roaming ‘armed reconnaissance’ (AR) missions seeking targets of opportunity behind the German front lines – these included road and rail infrastructure and especially ‘motorised enemy transport’ (MET) as well as tanks and armoured fighting vehicles (AFV’s). Many AR missions would be flown with the purpose of strafing road traffic with the Typhoon’s 20mm cannons.

Figure 4: Mission type and numbers for 143 Wing squadrons between 6th June and 31st August, 1944.

Over 90% of 143 Wing’s bombing targets have been resolved to 6-figure or 4-figure map coordinates or a specific place name. However, AR missions against road traffic can present a much greater challenge for the mapping exercise since it is sometimes the case that ORBs give only the general areas being flown relative to major towns (e.g. Falaise-Argentan-Bernay) and a list of vehicles claimed to have been destroyed (‘flamers’), seriously damaged (‘smokers’) or merely damaged (see example in Fig. 5). In these cases, we have included a strike marker on roads in the general vicinity of each town named on the AR mission log with a note that the locational details have yet to be verified. It is to be hoped that some of these strikes will be resolved to more specific locations if more information is forthcoming - until then they are included here in order to show the general geographical range and objective of the mission in question and should be treated with due caution!

Fig. 5: Extract from 439 Squadron ORB for the 19th August, 1944.

Analyzing the day-to-day location and details of ground attacks reveals the changing nature of tactical air operations by 143 Wing over the course of the Normandy campaign (Fig. 4). While dive-bombing attacks were the primary mission type during all three months of the campaign, the marked rise in AR missions during August reflects the transition to an increasingly mobile campaign following Allied breakout operations and the greater opportunities to attack German traffic obliged to move in daylight. Also striking is the predominance of missions to the south and east of Caen and Bayeux, reflecting the nominal role of 143 Wing (as part of 83 Group, Second Tactical Air Force) as supporting the British Second Army. On occasion, however, the Typhoons were deployed further afield and sometimes in direct support of US forces, notably on 7th August (MissionID 440807001) as part of operations against the German counter-attack in the Mortain area (Operation Lüttich).

Typhoon on the prowl

Integrating this data with the Project ‘44 database also allows us to estimate the distance between targets attacked and the contemporary front-line. This reveals the considerable geographical range of missions that took 143 Wing Typhoons well beyond the front-line and deep into the German rear areas (Fig. 6). Excluding the Noball raids of 20th June, these could be as far as 120 km distant from friendly troop positions, and on average were respectively 13 km and 26 km beyond the front line for dive-bombing and AR missions. Indeed, only around 40% of bombing missions against pre-planned targets occurred within 5 km of the front-line. Many of these close support missions were guided by smoke marking from Allied artillery, and on occasion, these were sufficiently successful and decisive enough to earn a commendation from Army commanders. Only once do the ORBs admit to an episode of mistaken target identification and an attack on friendly troops - that of a 439 Squadron mission on the 6th August (MissionID 440806003). Notwithstanding this particular episode, the ORB (Summary of Events) entry of 24th June for 438 Squadron suggests that the pilots preferred these sort of close support missions:

‘The third (operation) made with nine aircraft was part of a Wing “do” against strong points near Caen as Army Co-op work. The bombing was excellent and this Squadron received a commendation from the Army on the job. This is the type of target which the boys revel in, rather than attacks on railways, bridges, etc.’

Figure 6: Distance of 143 Wing ground attack strikes from the front line, 6th June – 31st August 1944.

Finally, turning to our initial motivation for the study, we have been able to identify 68 raids (19% of ground attack missions) that were made against targets concealed in woodlands. This aspect of the work is at an early stage, but it is noteworthy that all three of the sites chosen for initial archaeological survey have been found to preserve bomb craters that are likely to include (or are solely the work of) 143 Wing aircraft. One of these sites was a fuel dump in the Forêt de Grand Gouffern, located 6.5 km east of Argentan and attacked by 439 and 440 Squadrons early on the 25th July (see MissionID 440725005 and 440725006). Nineteen Typhoons dropped a total of 38 1000 lb bombs along the side of a road running north into the forest from Silly-en-Gouffern and, although no explosions were observed (suggesting perhaps that the dump had been moved by the time the raid arrived), evidence of bomb craters can be seen on aerial photographs taken shortly after the war and many still survive amongst the trees today (Fig. 7). Further work at these sites will seek to conduct full surveys of the impact areas (and to check for records of any other Allied aircraft who may have attacked the sites) so that these cratered landscapes can be added to the archaeological record and broader heritage of RCAF action in Normandy.

In due course we hope to extend this work to a much larger sample of Allied units flying with the US Ninth Air Force and RAF Second Tactical Air Force, and thereby develop a better picture of the variety of nationalities, aircraft types and mission characteristics associated with tactical air power in ground attack operations across the Normandy battlefields.

Figure 7: (A) Aerial photograph (1947: IGNF_C1714-0021_1947_F1714-1815_0222) showing part of the Forêt de Grand Gouffern bombed by 439 and 440 Squadrons on 25th July, 1944. Note bomb craters to west of N-S road. Inset frame shows location of bomb crater No. 2 (of 11 surveyed to-date) shown in photograph (B). Crater is 5 m in diameter (photo: DC-T).

About the Authours:

Dr David G. Passmore is a sessional lecturer in Geography in the Department of Geography, University of Toronto Mississauga, Canada. He is a geoarchaeologist with interests in conflict archaeology, military geography and history, environmental change and cultural resource management. His current focus is on Second World War landscapes in the forests of northwest Europe.

Email: david.passmore@utoronto.ca

Dr David Capps-Tunwell MBE is retired from the Royal Navy after a career in aircraft engineering and IT. He now lives in Normandy, France and is an associate member of the University of Caen. He is currently researching the effect of intelligence gathering operations carried out by Special Air Service on Allied tactical bombing during the battle for Normandy using archive sources and geoarchaeological analysis of landscape evidence.

Email: david@transform.fr

[1] Capps-Tunwell, D., Passmore, D.G. and Harrison, S. (2016). Second World War bomb craters and the archaeology of Allied air attacks in the forests of the Normandie-Maine National Park, NW France. Journal of Field Archaeology, 41(3): 312-330.

[2] Passmore, D.G. and Capps-Tunwell, D. (2020). Conflict archaeology of tactical air power; the Forêt Domaniale de la Londe-Rouvray and the Normandy Campaign of 1944. International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 24: 674-706.

[3] Available online at the Héritage project, a collection curated by Canadiana in partnership with LAC and the Canadian Research Knowledge Network.

[4] Halliday, H.A. (1992). Typhoon and Tempest: The Canadian Story. Toronto, CANAV Books.

[5] Hilton, J. (2015). The Saga of a Canadian Typhoon Fighter Pilot. Jack Hilton.

[6] The National Archives (TNA) AIR 37/713.