The Maritime Defence of Canada during the Second World War

1939 to 1945

©Roger Litwiller

Canada formally declared war on Germany on September 10th, 1939, seven days after Great Britain and France. Despite the delay, the Canadian military and especially the Royal Canadian Navy had already been on a war footing since 26 August, when the RCN placed all merchant shipping under the control of the Navy.

In the early days of the Second World War, there were two primary threats to Canada, both from the German Navy. The Kriegsmarine had focused on building surface raiders during the inter-war years. This consisted of fast heavily armed “pocket-battleships,” capable of appearing anywhere and with their six 11-inch guns could easily sit off Halifax and indiscriminately shell the city, harbour, and port facilities with impunity. Germany had also built several commerce raiders; these were merchant ships with guns and weapons concealed in the hull and superstructure. Capable of camouflaging their identity to resemble well-known allied ships, these commerce raiders would sail up to an unsuspecting ship and once close, reveal its guns and sink its unsuspecting prey.

The other major threat to Canada was the German U-boats. During the latter part of the First World War, six large ocean-going U-boats attacked shipping off the coast of Canada. With the advancement of submarine technology after WWI, hostile U-boats operating in Canadian waters were expected to commence immediately on the outbreak of war.

The Maritime Defence of Canada took a multi-level, sea, land, and air approach involving forces from the Royal Canadian Navy, Canadian Army, Royal Canadian Air Force, Department of Transport, and other federal Government departments and agencies.

BUILDING A NAVY

Royal Canadian Navy

The RCN started the war with six destroyers and five minesweepers, not enough to protect the coasts of Canada and provide escorts to the convoys sailing from Halifax to the UK. The RCN had started preparations for war in 1937, identifying government vessels that could be taken over by the navy and quickly armed from stockpiles of naval weapons located at the naval bases in Halifax and Esquimalt.

In September 1939 the first of 20 ships from the Department of Transport, Royal Canadian Mounted Police Marine Unit, Hydrographic Service, Fisheries Protection Service, and other Canadian Government departments were transferred and commissioned into the RCN. Several of these ships were former minesweepers originally built for the RCN in the First World War. As the ships entered service they were assigned to coastal escort, harbour, and anti-submarine patrol, minesweeping, and examination service, allowing the few destroyers to be assigned directly to the Atlantic, escorting convoys of merchant ships.

All ports came under the control of the RCN and additional Naval Bases were established at Sydney and Shelburne in Nova Scotia, Saint John, New Brunswick, and Quebec City, Montreal, and Gaspé in Quebec. Each had a Naval Officer In Charge (NOIC), responsible for harbour protection, movement of shipping in their area, and the examination of merchant shipping.

Protection of the ports was accomplished by the RCN utilizing a combination of seaborne and fixed defences. All potential entrances to a harbour were blocked except for one primary channel. Harbour defence ships would perform anti-submarine asdic patrols of the channel, harbour approaches, and the convoy assembly area outside of the harbour, while minesweepers would routinely sweep the marked channels and the area outside of the harbour. Large anti-submarine and anti-torpedo nets were laid across the entrance to the harbours and operated by Gate Vessels as required. An inspection ship was kept outside of the anti-submarine net to confirm the identity and cargo of ships attempting to enter the harbour.

Additional defences were added in some harbours, consisting of controlled minefields on either side of the netting, submarine detection loops, and fixed submerged asdic units. In 1940, Halifax received the first shore-based radar in Canada. Located on both sides of the channel, the two sets were able to sweep the channel and harbour entrance and proved very useful in determining positions of shipping at night and in heavy fog.

Halifax remained the primary base for naval operations on the east coast and also became the primary convoy assembly and control point. When the defence of Newfoundland became a Canadian responsibility a large naval base was built in St. John’s with defences.

Facilities for local convoy escorts were built at Sydney and the Cape Breton harbour became a convoy collection point during the summer months, providing some relief to Halifax. As U-boat operations moved closer to Canada, ocean escort forces were moved to St. John’s NF.

Construction of an escort base began at Gaspé for the Gulf and St. Lawrence Escort Force and was operational by the time the U-boats began hostile operations in the St. Lawrence in early 1942. The Gaspé Naval Base took on additional importance as the planned home for the remaining Royal Navy fleet if Britain was forced to surrender during the expected invasion after the fall of France in 1940 and again later when the U-boats nearly accomplished what the Luftwaffe could not, the starvation of Great Britain during the darkest days of the Battle of the Atlantic in 1941 and 1942.

Smaller ports at Louisburg, Cape Breton, and Conception Bay on Bell Island in Newfoundland also received Anti-Submarine netting and defences later in the war.

The Canadian Army

The armed defence of strategic coastal communities in Canada began in the colonial occupation of North America by the French and English; large fortifications were built at Quebec City, Halifax, and Louisburg. Later additional fortifications were built along the coast and Great Lakes to defend against attacks from the United States during the War of 1812. With Confederation, the defence of Canada became the responsibility of the Canadian Army, and with the US no longer a threat many of the fortifications fell into disrepair or were abandoned.

During the First World War, the protection of Canada’s ports and harbours took on a new importance and old fortifications were brought up to standard. With the armistice in 1918, again fortification of the Canadian coast fell in priority.

As the international political climate changed in the 1930s, the Canadian government’s assessment showed Japan was the greatest potential threat of hostilities, and fortifications on the west coast took priority. In 1937, there was a limited number of shore guns available in Canada and the established forts at Halifax and Quebec City were stripped of most weapons to reinforce Esquimalt, Vancouver, and Prince Rupert.

By 1939 Germany was demonstrating a renewed threat to Canada’s east coast and new fortifications were built and old forts upgraded at Halifax, Quebec City, Saint John, NB, and Sydney, NS.

The Army’s port fortifications were built as a multi-level defence. Several long-range gun emplacements were built at the approaches to the respective harbour usually consisting of two or more 9.2-inch guns, with additional, smaller rapid-fire 6-inch or 4.7-inch guns inside the harbour approaches to engage the enemy at close range. Searchlights were installed with the gun positions with large 60-inch wide beam lights to sweep the ocean for targets and bright concentrated beam lights to pinpoint a target for the guns.

The gun and searchlight emplacements were built of concrete for protection against enemy fire. Several tactics were employed to camouflage the fortifications. The larger guns were built either in a steel turret above ground or on disappearing carriages. When not in use the gun rested in the concrete emplacement below ground level, when ready to fire the carriage would lift the gun above the grade, shoot and return below grade to reload. The smaller guns and searchlights were built into the cliffs and rock walls of the harbours, making them undetectable from the sea.

Perhaps one of the more ingenious techniques utilized was to camouflage the fire control positions and the gun range-finding optics by building elevated structures that resembled churches, lighthouses, or multi-level houses in concrete. The tall steeple with heavy steel doors facing the water provided an unobstructed view. In the lower part of the structure were the headquarters, stores, and workshops. One of the best examples of this type of coastal fortification can be visited at Fort Petrie near New Waterford in Cape Breton. Magazines were built in reinforced concrete structures underground, behind the gun emplacements.

For almost all of the fortifications, the only shots fired during the war were for training purposes or the occasional warning shot fired across the bow of a merchant ship, whose errant skipper did not obey the orders given by the examination vessel.

The exception was the Bell Island Battery located at Wabana in Conception Bay, NF. The ore docks were attacked twice; first U-513 entered the Bay and sank SS Lord Strathcona and SS Saganaga on 5 September 1942. Then on 2 November, U-518 torpedoed SS Rose Castle and the Free French Freighter PLM 27. The Battery opened fire on both U-boats, but the mounts did not permit the two 4.7-inch guns to depress low enough to engage effectively and both submarines escaped. Sixty merchant sailors were killed and another 120 survived the two attacks.

The Army’s defences were further increased with the installation of Radar Sites along the Eastern Seaboard. The first land-based radar installed by the RCN at Halifax in 1940 had proven exceptionally useful in tracking shipping, especially at night and in fog, when the observation posts for the gun emplacements were blinded.

The National Research Council had been developing better radar sets since the onset of the war and in 1941 an order was placed for 20 radar sets for stations along the Eastern Seaboard. As the Army was responsible for the defence of the harbours from surface attack and the radar was far superior in tracking and plotting the range and position of surface vessels than the existing optical range finders, the 20 radar sites, as well as the RCN sites at Halifax, were turned over to the Canadian Army.

Royal Canadian Air Force

The Royal Canadian Air Force was the youngest of the three armed services and in 1939 celebrated its 25th anniversary. When war was declared in September there was only one operational maritime defence squadron in the Eastern Air Command, No. 5 General Reconnaissance (GR) Squadron RCAF was based at Dartmouth, NS, flying Supermarine Stranraer’s. The Flying Boats had a limited range of 200 miles and provided air escorts to the first convoy, HX-1 to leave Halifax. By establishing fuel dumps at Sable Island the range was extended to 400 miles for the second convoy.

Consolidated Catalina or Canso over Fairmile on exercise at Gaspé, June 1943

Air cover for convoys was essential to the protection of merchant ships. A single aircraft over the convoy forced the U-boats to remain submerged, fearing an attack. On the surface, a U-boat commander could race around the convoy to be in a good attack position when darkness came. Submerged the U-boats decreased speed could not keep up with the convoy and contact would be lost.

Early in the war, long-range aircraft were not available as new planes were diverted to the European theatre for missions over Germany. This left a vast expanse of the Atlantic Ocean without air cover, sailors called this area the “Black Pit.” Packs of U-boats hunted the convoys, sinking merchant ships with only the navy’s escort ships to protect them. At times a convoy escorted by an escort group of six warships, consisting of one or two destroyers with a mix of frigates and corvettes would face over 20 U-boats in a sea battle that would span the entire Atlantic over several days. The German submariners called this the “Happy Time.”

As losses mounted on the Atlantic, the need for maritime patrol aircraft became a priority, additional Maritime Squadrons were formed and new airfields were constructed for the RCAF throughout the Maritimes, including, Sydney, Yarmouth, and Greenwood in Nova Scotia, Gander, and Torbay in Newfoundland and in Quebec at Gaspé.

Nine Maritime Squadrons were formed, flying Ventura, Bolingbroke, Hudson, Canso, and Liberator aircraft. The increased range of the Canso and Liberator aircraft closed the Black Pit by 1944, providing air cover to the convoys from Canada to the UK.

RCAF in Canada

Airfields were built across Canada for training and defence. Learn more about the Air Defence of Canada at the link below.

Department of Transport

The Canadian Department of Transport was responsible for safe navigation in Canadian waters, including aids to navigation, buoys, beacons, lighthouses, lightships, icebreaking operations, marine communications, radio direction finding, and marine search and rescue. The DOT’s workforce consisted of highly skilled civilians, working from shore establishments throughout the country and a large fleet of Canadian Government Ships.

Unlike Canada’s Armed Forces, the DOT did not suffer serious financial cutbacks following the First World War and operated some of the newest and most technically advanced equipment available. The significant contributions to the war effort by these civilians are often overlooked.

One of the most important contributions was made by the DOT Marine Radio and Direction Finding Stations, located along both the Pacific and Atlantic coasts. On the outbreak of hostilities the stations were transferred to the RCN, The DOT operators continued to work at the stations and were augmented by naval staff. When the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service was established in 1942, many of the Wrens were assigned to the stations.

Utilizing the most advanced communication equipment, these stations were already tracking the locations of German U-boats on the Atlantic on 3 September 1939. Every time a U-boat made a radio transmission, two to three direction-finding stations would triangulate the source of the signal, pinpointing the location. The position was then transmitted to Naval Service Headquarters and Naval Forces were alerted. Additionally, the radio messages were recorded and when the Enigma Code was deciphered the information in the transmission was passed on. The Radio Station located at Hartland Point in Nova Scotia played an instrumental role in locating the German Battleship Bismarck, allowing Naval Forces to find and sink it.

A coastal watch system was organized by the Department of Transport and the RCN, all lighthouse keepers on the eastern seaboard, Gulf of St. Lawrence, and St. Lawrence River received training in identifying German surface ships and U-boats. Several lighthouse keepers in the St. Lawrence did spot and report U-boats in their area. When a U-boat was known to be in an area, a plan was developed between the DOT and RCN with the cooperation of CBC Radio broadcasting, a code word was transmitted by CBC Radio instructing the lighthouse keepers in a respective area to immediately douse the lights and stop all fog signals until an “All Clear” signal was broadcast.

The Canadian Government Icebreakers had an important role in extending the shipping season by keeping the shipping lanes, channels, and ports ice-free, allowing merchant's ships to load the precious cargo and permitting newly built corvettes and minesweepers from the shipyards in the Great Lakes to escape the winter freeze and begin service on the Atlantic.

The civilian population all along the coast became witness to the fierce fighting offshore, especially in the St. Lawrence where convoy battles between naval and merchant ships were fought with German U-boats within sight of the shore. U-boat identification posters were put up in post offices and public buildings all along the coast.

The importance of the Defence of Canada has been overlooked when discussing the history of the Second World War. Popular history is of course told through the actions that were fought in Europe. Ultimately, it was the successful defence of Canada’s coast that allowed the thousands of merchant ships transporting the materials to fight the war in Europe to successfully arrive in the UK. The German Navy and especially the U-boats were very capable of offensive operations in any theatre of the war and the coast of Canada was no exception.

Both Halifax and St. John’s, NF had U-boats lay minefields outside of the harbours, sinking several ships, twice the ore facilities at Bell Island came under direct attack. Perhaps one of the most daring attacks was by U-587 firing four torpedoes into the cliffs of the harbour, in a failed attempt to block one of the most important harbours in the Atlantic.

On two occasions, U-boats landed spies in Quebec and New Brunswick, while a third set up a remote weather station on the northern tip of Labrador.

In addition to these attacks, there were hundreds of merchant ships and escort ships attacked on Canada’s coasts, the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and the River. U-boats operated as far west as Rimouski in Quebec. In the final weeks of the Second World War, when the German army was in full retreat, the U-boats were still able to conduct aggressive offensive operations on Canada’s shores.

It was the concerted, cooperative operations between the RCN, RCAF, Canadian Army, and Department of Transport that protected the harbours, shipping lanes and the convoy routes along the coast that eventually led to Victory in Canada.

Support the project:

How can you support the project:

Buy a map today!

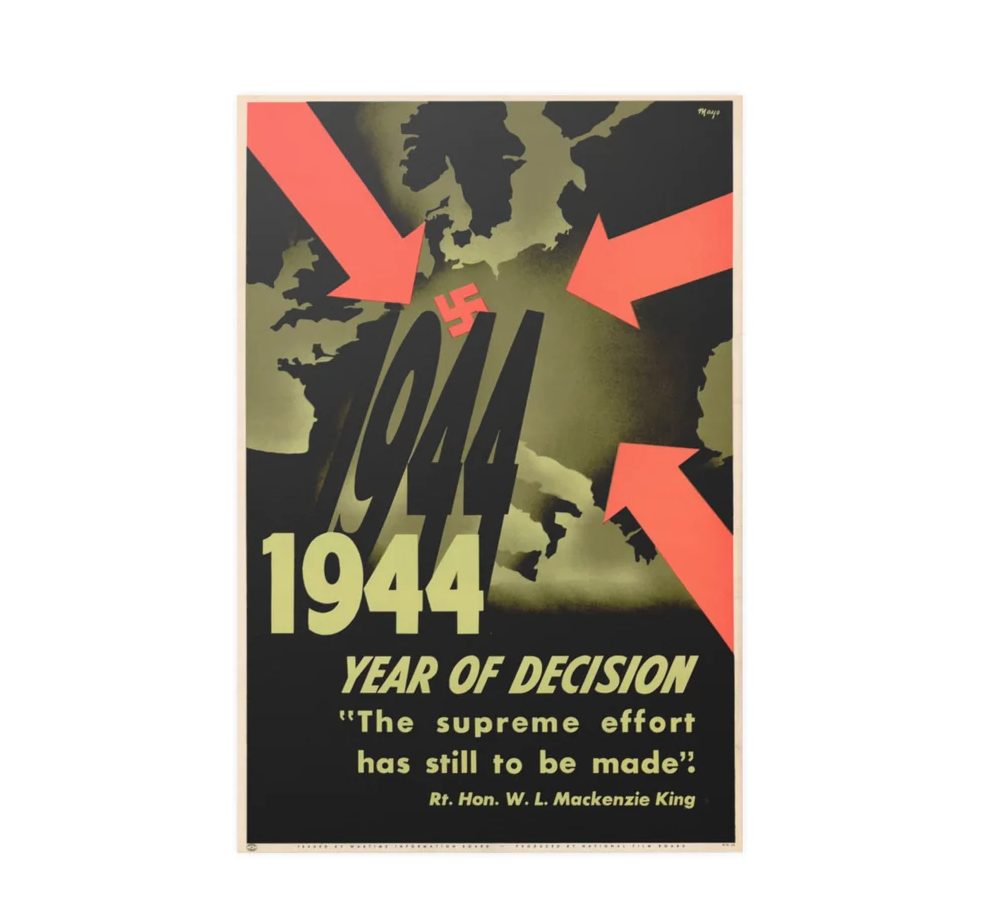

We sell many authentic posters from the Second World War.These are high resolution scans of original posters that you can only find in the archives.

Each poster is printed on high quality paper ready for mounting in a frame for your office or living room.

The best part of buying a poster? 100% of proceeds are directed back to the project allowing us to continue to map out the Second World War.

Other ways to support the project:

Donate

You can help us tell the story of Canadian soldiers by donating today!

Our team is dedicated to keeping the story of Canada in the Second World War at the forefront using interactive technology that makes history open and accessible.

With your donation you help us to keep mapping and digitizing war diaries so we can continue to tell the story of those who served and those who fell.

Join Patreon

Do you want to become part of the team? Consider joining Patreon!

As a member of Patreon you can influence our project, what we are working on, and can even direct message our team. As a Patreon you can even get discounts to our entire store!

With your membership you can show your commitment to the project by helping us every month. And the best part is, every Patreon dollar goes directly to the web map!