Japanese-Canadians were almost immediately targeted when war broke out in the Pacific

During the Second World War, 21,000 people of Japanese ancestry, the majority of whom were born in Canada or were British subjects, were dispossessed, relocated, and interned by the Canadian government. Their lives were ruined by a reactionary policy with no basis in fact.

As a result of the attack on Pearl Harbor panic spread among the inhabitants of Canada’s west coast about a possible Japanese invasion in late 1941. This panic, combined with decades of racist treatment toward people of Japanese descent, led to drastic measures being taken against Japanese Canadians. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police moved quickly to arrest suspected Japanese operatives, while the Royal Canadian Navy impounded 1,200 Japanese Canadian owned fishing boats. Japanese newspapers and schools were voluntarily shut down due to harassment and a racist backlash.

As a result of this panic, the Canadian federal cabinet issue Order-in-Council P.C. 1486 on the 24th of February 1942. It ordered the expulsion Japanese Canadians residing within one hundred sixty kilometers of the Pacific coast. Using the War Measures Act, the government dispossessed, forcibly relocated, and interned many people of Japanese ancestry.

The week after the Order-in-Council was issued, the British Columbia Security Commission was established. It implemented and carried out the dispossession, relocation, and internment of Japanese Canadians on the west coast.

Across British Columbia a 160km exclusion zone was established forcing all Japanese Canadians out and into internment camps across the province.

Relocation

On the 16th of March 1942, the first Japanese Canadians were taken from several areas within the 160 kilometres exclusion zone. More than 8,000 detainees were brought to and were processed at Hastings Park in Vancouver, British Columbia. Afterwards, trains carried the detainees to places in the interior of British Columbia such as Slocan, New Denver, Kaslo, Greenwood, and Sandon. Around 2,150 single men were sent to work on road labour camps in various places in the interior.

Another 3,500 Japanese Canadians opted to sign contracts to work on sugar beet farms outside British Columbia. Working on the farms allowed families to stay together. Conditions on the sugar beet farms was horrendous. Labourers were crowded into shacks and other farm buildings. They were paid little for their labour.

Some 3,000 more affluent Japanese Canadians were allowed to leave the exclusion zone in groups and create “self-supporting projects” at their own expense.

Dispossession

Another order-in-council was signed of the 19th of January 1943 that liquidated all Japanese property that had been under the government’s “protective custody.” Homes, farms, businesses, and personal property were sold for pennies on the dollar. Some of the proceeds were used to pay the costs of detaining Japanese Canadians while some of these funds were held by the government, who refused to give them back to their rightful owners.

Internment

The majority of Japanese Canadians who were relocated, some 12,000 people, were exiled to the Slocan Valley, in British Columbia’s eastern Kootenay region. They were housed in what were called “interior housing centres” located mainly in largely abandoned mining towns or in a government-built camps. These were not camps surrounded by barbed wire or guarded. Individuals could move around but their actions were still limited.

Once moved to the Slocan Valley, the internees lived in abandoned dilapidated houses or in newly built shacks. The housing did little to protect against the weather. The Canadian government did not provide the inmates with any financial assistance, food, or clothing. No schooling above the elementary level was given. A few Christian groups opened high schools in the settlements. The government hired some individuals to cut wood and carry out other menial tasks, but in general people had to find their own work or live off their savings. The funds generated from the forced sale of their possessions was kept from the individuals.

End of the War

Controls on Japanese Canadians continued past the end of hostilities with Japan. Individuals were given the choice to either move to provinces east of the Rocky Mountains or be sent to Japan. In 1946, nearly 4,000 former internees left Canada for Japan. The policy was later dropped after public pressure.

Businesses and properties remained under government control. Movement was restricted until the 1st of April 1949, when Japanese Canadians were finally allowed to return to the West Coast, almost four years since the end of the war.

Apology and Financial Reparations

During the 1970s, Japanese Canadians began to organize remembrance and educational campaigns. The National Association of Japanese Canadians and other groups started a campaign for reparations for the dispossession, forced relocation, and internment of many Japanese Canadians during the Second World War.

In 1988, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney apologized on behalf of the Canadian government for its wartime against Japanese Canadians. The government also made payments to individuals and organizations. Each survivor was given $21,000. More than $12 million was allocated to a community fund for education about the internment and other human rights projects. In a symbolic action, the War Measures Act, the legal device used against Japanese Canadians, was repealed.

The Morishitas and Ebisuzaki family had been in Canada for more then 30 years when their business and homes were seized and they were forced to move.

Support the project:

How can you support the project:

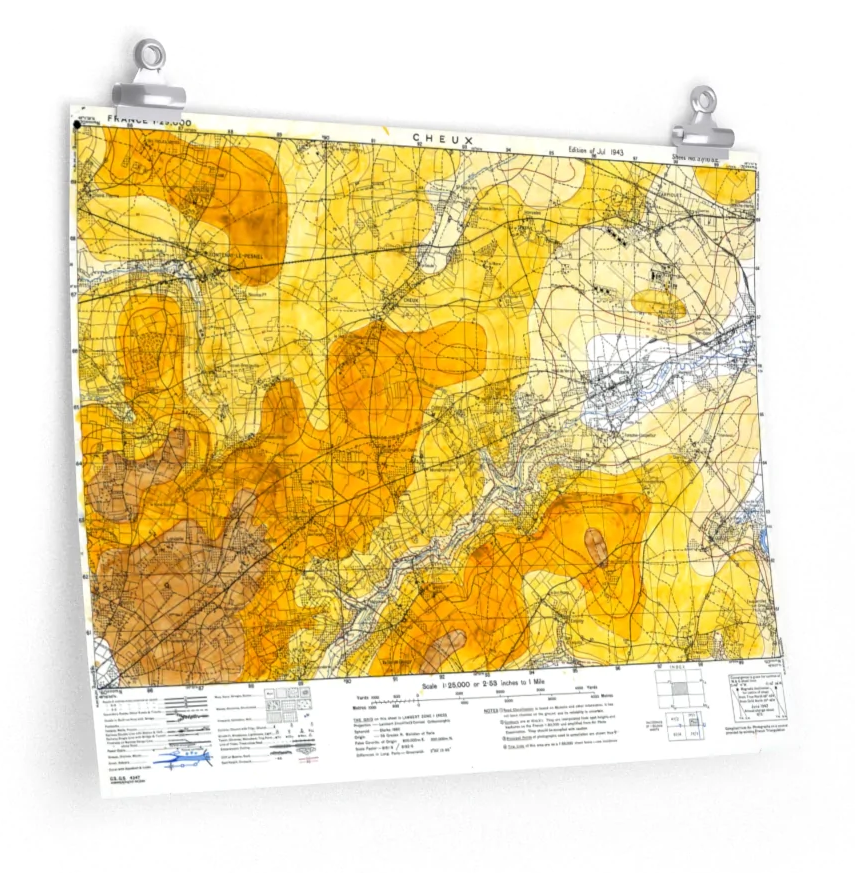

Buy a map today!

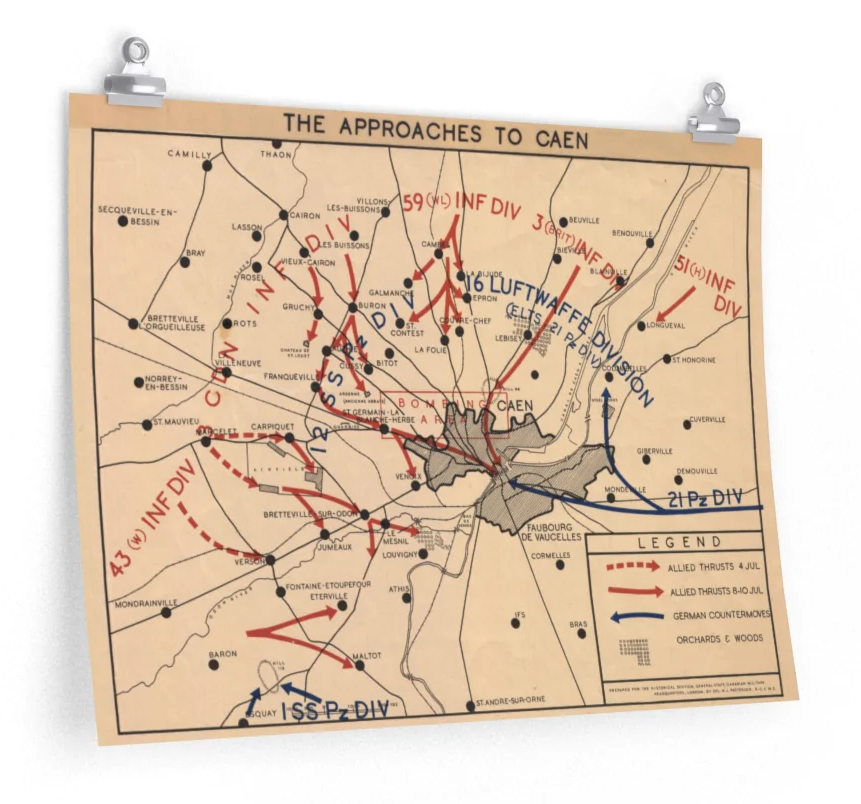

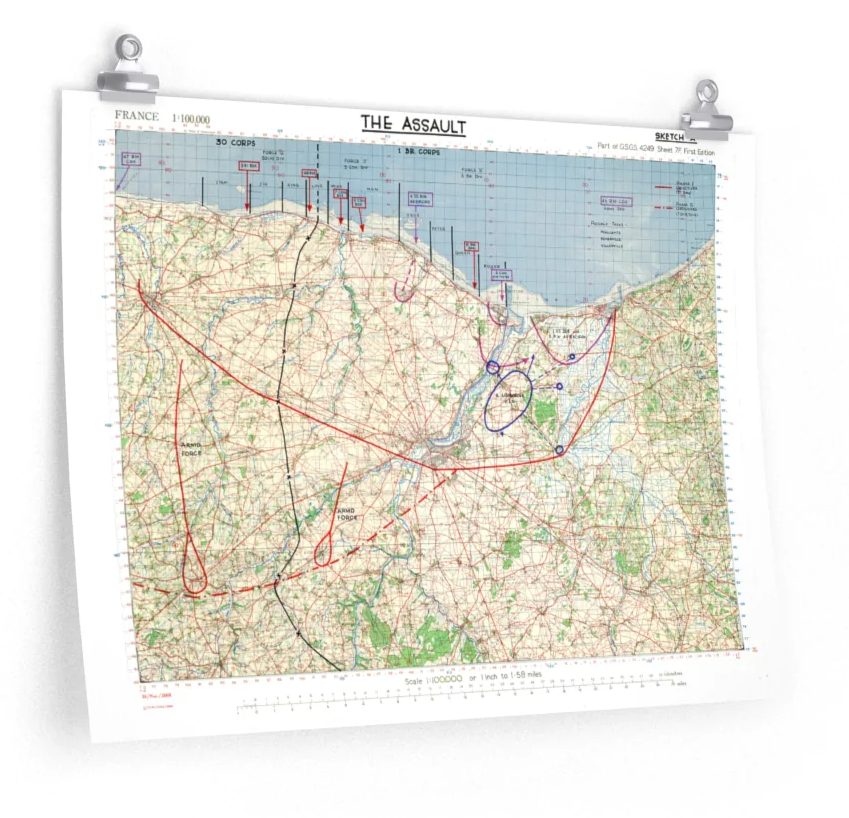

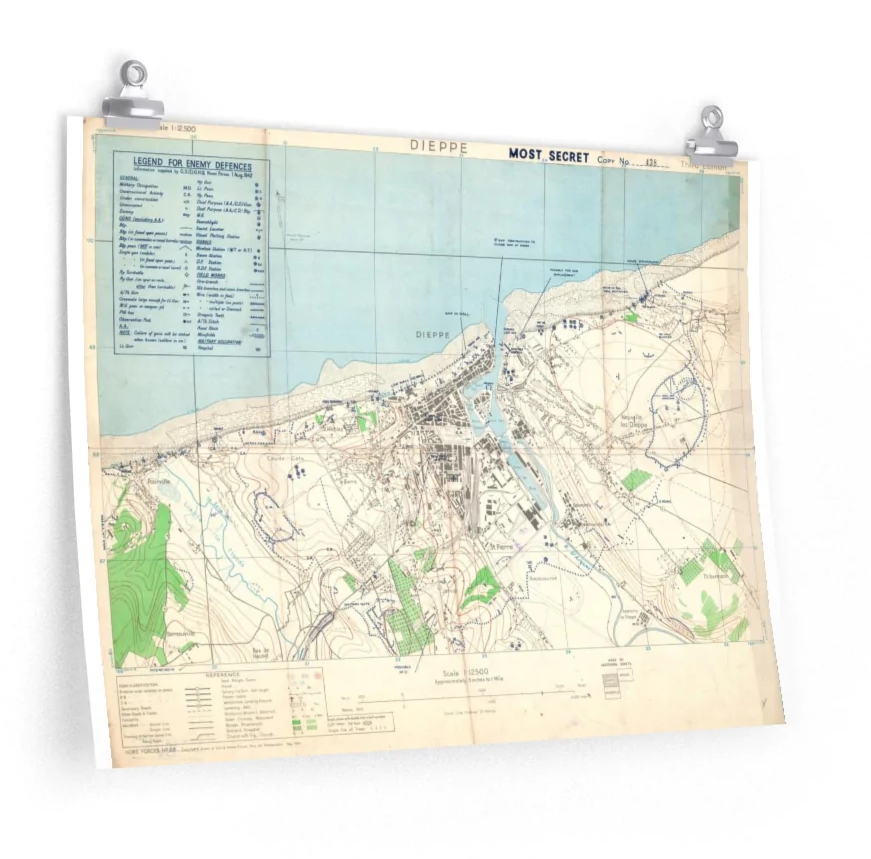

We sell dozens of authentic maps covering DDay, Monte Cassino, Dieppe, Market Garden and more. These are high resolution scans of original maps that you can only find in the archives.

Each map is printed on high quality paper ready for mounting in a frame for your office or living room.

The best part of buying a map? 100% of proceeds are directed back to the project allowing us to continue to map out the Second World War.

Other ways to support the project:

Donate

You can help us tell the story of Canadian soldiers by donating today!

Our team is dedicated to keeping the story of Canada in the Second World War at the forefront using interactive technology that makes history open and accessible.

With your donation you help us to keep mapping and digitizing war diaries so we can continue to tell the story of those who served and those who fell.

Join Patreon

Do you want to become part of the team? Consider joining Patreon!

As a member of Patreon you can influence our project, what we are working on, and can even direct message our team. As a Patreon you can even get discounts to our entire store!

With your membership you can show your commitment to the project by helping us every month. And the best part is, every Patreon dollar goes directly to the web map!