Sgt Moe Hurwitz - Part 1: 17 Handkerchiefs

By Author Ellin Bessner

Samuel Moses “Moe” Hurwitz was born on January 28, 1919, just two months after the end of the First World War. He was the eighth child of thirteen born to Bella and Chaim (Hiram aka Harry) Hurwitz, of Montreal. Moe’s parents were Jewish immigrants who had each arrived in Canada at the beginning of the 20th century.

The Hurwitz family lived in the borough of Lachine, a heavily industrialized area west of downtown Montreal. A tiny Jewish community established itself in Lachine before the First World War. They worked as tradesmen, labourer, and shop keepers. They were nearly all immigrants who had come to Canada to escape anti-Semitic pogroms in Tsarist Russia. They were vastly outnumbered by the majority French-Canadian and British neighbours.

Moe Hurwitz Bar Mitzvah. Moe is centre row second from the left dressed in Blue.

Moe’s father started his own business, a hauling company, using horses and carts to make the deliveries. One of his clients was the CN Railroad. Before the invention of refrigerators, Moe’s father would also haul ice to be used in kitchen iceboxes. He went down to the shore of the St. Lawrence River and chopped ice blocks out of the frozen river.

Moe and his eleven surviving siblings (six boys and five girls; the oldest child Zelig had died as a toddler) grew up in an Orthodox Jewish home. Their mother, who was born in Latvia, observed the Jewish dietary laws about eating Kosher food. Moe’s father, who grew up in England, did not work on Saturdays for religious reasons, and regularly took the boys to synagogue services. However, Moe’s father was also passionate about sports. After Sabbath services ended on Saturday mornings, despite his wife’s disapproval, the patriarch would take the Hurwitz children to watch soccer and cricket and football games.

By the time of Moe’s thirteenth birthday in 1932, following Jewish custom, he had a “bar mitzvah” ceremony. The family gathered to watch him be confirmed as an adult in the Jewish faith. Moe recited special passages from the scrolls of the Old Testament.

The next year, Moe started as a freshman at Lachine High School. He also joined a hockey team, playing his first season as an amateur for the Lachine Bulldogs in the City and District Intermediate Hockey League.

Although Jewish immigrant families usually pushed their children to get a good education, Moe grew up during the height of the Depression. With such a large household to support, Moe did what many teenagers his age had to do: when he turned fifteen, he quit school after Grade 9 to find work.

By 1936, many of Lachine's Jewish residents had already moved away, preferring to live amongst their own people in the densely populated three-storey walk-up apartments along Montreal’s St. Lawrence Boulevard, known as “The Main”. That’s where the majority of the city’s Jewish residents lived in the interwar years. The part of the city at the eastern base of Mount Royal boasted nearly fifty synagogues, Jewish schools, bagel bakeries and the Young Men’s Hebrew Association community centre on Mount Royal Boulevard.

The Hurwitz’s would soon move to “The Main”, where they would feel more “at home”. The move became more urgent when life for Jews became more uncomfortable in Lachine. As Moe’s sisters were old enough to start going out on dates, anti-Semitic bullies chased the girls off the local tennis courts. Moe’s father was himself arrested and charged for assaulting a man who had made pro-Hitler remarks. The judge sided with Hurwitz, but fined him $2.

Canada was not a welcoming place for the country’s small Jewish community in the 1930s. Support for Hitler and Fascism was strong in parts of the country, and antisemitism was widespread at all levels of society. Prime Minister Mackenzie King’s government notoriously refused to accept a boatload of 900 Jewish refugees from Hitler’s Europe. There were race riots at a Toronto baseball game involving a Jewish team. Jewish families were not permitted to own property in some cities including Hamilton, and Winnipeg. McGill University placed restrictive quotas limiting the number of Jewish students at medical school.

Although Moe’s summers were spent competing for a local rowing club in Lachine, once he settled into their new home on Park Avenue, the teen spent the winters playing hockey. For two seasons, 1936-1938, Moe played right wing and defence for the Montefiore Red Wings, an all-Jewish team in the Mount Royal Intermediate League. His brothers George, Archie and Max played with him, as did a cousin. The Red Wings played at the Mount Royal Arena, which at one time was home to the Montreal Canadiens of the National Hockey League.

Jewish hockey team the Montefiores: Moe is to the right of the coach. Brothers Archie, George and Max and cousin Morris Diamond as noted under the pic all played hockey together.

When the team wasn’t practicing or playing weekend matches at arenas around the city, Moe and George worked at Distiller’s Corporation. The international liquor giant had a facility near Moe’s old Lachine house. The prominent Bronfman family of Montreal founded the whiskey and spirits producer and sold it only in 2000. Moe earned $22 a week there as a labourer.

When Moe’s hockey season ended every March, he and his brother George would throw themselves into their other passion: canoe racing in the St. Lawrence River. The Lachine Canoe Club had won the Dominion championship in 1930 and 1933, and their rowers were practically unbeatable. Moe spent his summers competing in several categories: as the pilot of intermediate fours, in junior single, and in the junior tandem race with his brother.

By 1939, Moe’s name was regularly featured in the city’s sports pages of the Montreal Gazette newspaper. Montrealers were reading about Moe’s success on the water, and even more about his success on the ice of the city’s hockey arenas. During one game now playing centre for the Villeray team, Moe scored four goals and had one assist.

He came to the attention of the coach of the Lachine Rapides, a senior men’s team in the Quebec Provincial Senior Hockey League. The coach was an executive at the Dominion Bridge Company, another major employer in Lachine. He offered Moe a job there as a labourer, with a nice raise in salary, to $27 a week. In return, Moe got a spot as an alternate on the Rapides bench.

As Hitler marched into Poland in the fall of 1939 and Canada declared war on Germany, Moe, then 20, spent his weekends travelling to games in hockey arenas in Ontario, southern Quebec and even the Northeastern United States.

The Rapides attracted a crowd of 2,200 fans when they played in their home arena in Lachine.

Attendance was four times that size when Moe and the Rapides arrived at the storied Boston Garden for a pair of games before Christmas against the Boston Olympics, the farm team of the Boston NHL club. Although the visiting team lost both matches, sportswriters in Boston took notice of one particular athlete on the rink.

“The untiring Moe Hurwitz was the bright star. Hurwitz, who alternated between forward and defence, bagged two of his team’s three tallies,” wrote Herbert Ralby in The Boston Globe. Moe also earned two penalties: one for charging and the other for playing without a stick. They weren’t the only times his talent for goal scoring combined with his aggressive personality got him noticed.

It was during a key playoff match in Boston later that season where Moe would rack up a goal but also a more serious penalty. With the chance to advance to the league final on the line on March 14, 1940, Moe was in the starting lineup for the game in Boston. He was playing right wing. At the start of the third period, a frustrated Boston defenceman, Bill Splaine, pinned Moe hard against the boards. The referee blew the whistle, but Moe quickly meted out his own justice. He dropped his gloves and started punching. Both players received major penalties before a crowd of 13,000 fans. The Rapides smashed their way past Boston 8-0 for the lopsided victory.

But the Rapides couldn’t beat Sherbrooke for the league season championships. Lachine lost.

With his hockey responsibilities on hiatus, Moe wasn’t without options for the rest of the summer. His steelworker job at Dominion Bridge was still there. So was canoe racing.

But he had caught the eye of the scouts for the Boston Bruins of the National Hockey League. There was an offer for the rugged young athlete to come to Boston for a tryout. This was a huge opportunity, and more so for a Jewish athlete, as there were fewer than a handful of Jewish players in the NHL.

But Moe’s attention was on the war in Europe. In May 1940, Hitler’s army captured Holland. The British had pulled off the stunning evacuation of hundreds of thousands of troops across the English Channel from Dunkirk as Germany captured France. In June, Canada announced a national registration of everyone between the ages of 16 to 60 for possible war service.

Moe turned the Boston team offer down, saying he was going to enlist.

“There’s no time to play hockey when millions of my brothers are getting killed in Europe,” he is reported to have told his family.

Two days after the French surrender, on June 24, 1940, Moe left his family’s Jeanne-Mance Street apartment (they had moved yet again) and made the twenty-minute walk south to 4171 Esplanade Avenue. The red-bricked Armoury was (and still is) home to the Canadian Grenadier Guards infantry regiment.

The Guards had just mobilized for active service in late May, which meant volunteers knew there was a strong chance they would be sent overseas instead of remaining in Canada to complete their army service during the war. That suited Moe fine.

At his medical evaluation, Moe weighed in at 5’ 7” and ¾ inches, and 156 pounds (70 kilos). He told the doctors he had an old injury on his right wrist, but it wasn’t going to prevent him from passing the exam. He told the Guards that he wanted to join up because of patriotism. He told his interviewers, he hoped to go back to work at his old job after the war and learn to be a machinist.

The Guards took him on strength at the lowest rank, Guardsman, with service number D-26248. But Moe would quickly progress through basic training. While at Camp Borden, north of Toronto, Moe earned promotion after promotion as he completed training using weapons, including Sten guns, pistols, rifles, Thompson machine-guns, Bren guns, PIATs, and grenades. The army liked what they saw in Moe, and he made Ssergeant in less than a year.

Moe and his brother Max

“Score not indicative of ability as a crew commander. Has aggressiveness. NCO likes army work, likes his men. Knows them as an NCO should.”

Many of Moe’s siblings also joined the war effort. All six of his brothers and one sister put on a uniform or tried to. In 1940, Moe’s unit, the Grenadiers, turned away his brother Harry. Harry was two years younger, and two inches shorter. He had only a Grade 7 education. Undaunted, Harry snuck onto a westbound freight train, got off in Picton, Ontario, and joined the Army’s Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment. He lasted a year, then transferred to the Navy.

Dave Hurwitz travelled to California, where he joined the U.S. Army. George was rejected due to a bad back. Max served as a sapper with the Royal Canadian Engineers overseas, Archie (Aaron) was in the Royal Canadian Air Force. Ian Hurwitz was with the Royal Canadian Navy. Baby sister Esther enlisted in the Canadian Women’s Army Corps.

In January of 1942, the Grenadier Guards became an armoured regiment, and Moe was sent off to take training on tanks. By spring, he had qualified as a Sherman tank driver and was also a gunnery instructor at the Canadian Armoured Corp’s training courses held at Camp Borden.

His superiors praised Moe’s handling of himself and how he dealt with his men as a Troop sergeant.

Just after the Jewish New Year in September 1942, Moe shipped out for England, arriving on October 7 as a full sergeant with the newly named 22nd Canadian Armoured Regiment (Canadian Grenadier Guards). While the tank crews were getting settled in England, Moe missed his brother George’s October wedding, and the family’s move to yet another new apartment, this time at 6093 Park Avenue.

Moe and his men spent the next 18 months training with their tanks and on manoeuvres in the forests and plains of southern England. He went to tank school in Bovington in 1943, near Dorset, where he qualified with distinction as a crew commander. His superiors wrote that he was “indefatigable and energetic to a surprising degree”. Upon his return to the Canadian camp at Crowborough, Moe was kidded about his success. He deflected the praise.

“While the English lads were reading the task system to see how it should be done, I went over and did the job,” writes Major Ian Phelan of the same regiment in a pamphlet dedicated to Moe and published after the war.

Months went by while the highly trained Canadian troops waited impatiently in England for a chance to enter battle. Moe and Phelan spent many hours talking about what waited for them when they landed on the other side of the English Channel. Phelan remembers Moe being anxious for his men, and worried he might fail them.

“Such was his modesty,” Phelan would write. Moe, he added, displayed “a strain of courage and steadfastness and human-ness...that put to shame the tinsel heroes of the silver screen.”

Moe was also thinking about the letters “Heb.” engraved on his military identity discs, which revealed he was a Jew. In the face of possible capture by the Nazis, who were methodically annihilating six million European Jews in the Holocaust, Moe vowed he would never allow himself to be taken prisoner.

Sgt Moe Hurwitz DCM MM

Six weeks before D-Day in April 1944, Moe’s brother Harry (birth name Hirsch but like his father always called Harry) was manning a forward gun on the Canadian navy’s destroyer HMCS Athabaskan when a German vessel torpedoed her off the Brittany Coast. Harry survived the sinking by clinging first to a piece of the ship’s mast for four hours in the oily water and then climbing into a life raft. He was taken prisoner and sent to a German POW camp, Marlag and Milag North, near Bremen. When the news reached Moe in England, it made him more determined than ever to get into combat, and save Harry.

“He was going to fight the whole German army to save me,” Harry Hurwitz told interviewer Ellin Bessner in her 2019 book “Double Threat”.

Moe’s regiment would have to wait until nearly the middle of July 1944, nearly six weeks after D-Day. Word came that the 22nd Canadian Armoured Regiment was to sail across the Channel for Normandy. As the tanks and men moved into position at the London docks to board their transport ships, bad luck struck. On July 20, a German V-1 flying bomb landed in front of the procession, killing the Guardsman at the wheel. It was a taste of what was waiting for them when they landed in France.

Phelan noted that it was on the tense trip across the Channel that Hurwitz began to grow a moustache. The facial hair combined with his big hands, square jaw, and dark eyebrows gave Moe, by now 24, a fierce look. It didn’t hurt that he had also put on some extra muscle since joining up three years earlier.

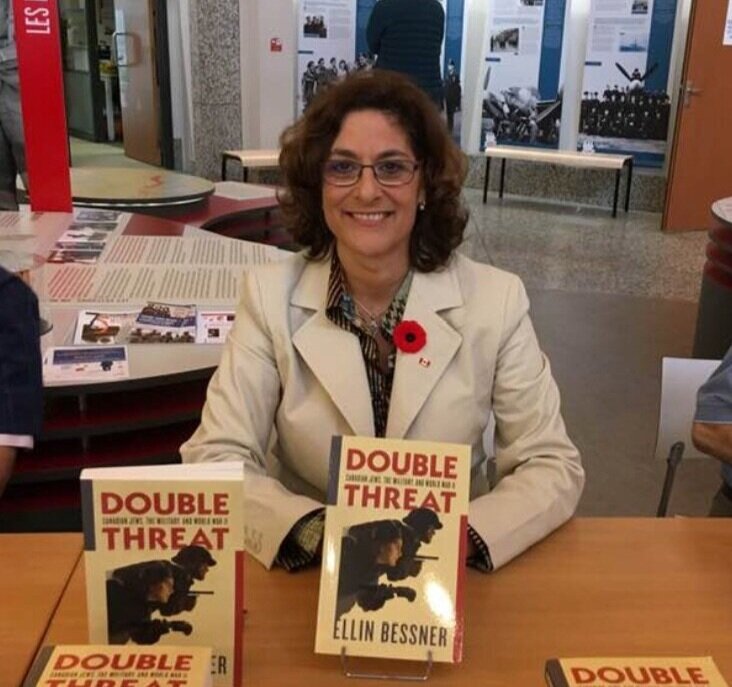

Ellin Bessner is a Canadian journalist and author. Montreal was home but Ottawa’s Carleton University provided the education in journalism and political science. Ellin has worked for CTV News, CBC News, the Globe and Mail, the Canadian Press and more. Her assignments have taken her through Canada, Europe and Africa. Ellin also teaches journalism at Centennial College.

She recently authored the book “Double Threat: Canadian Jews, the Military and WWll” (2019). Her work prompted Veterans Affairs Canada to recognize the contribution of Canada’s Jewish community to the country’s military history.

Ellin lives with her husband and two sons in Richmond Hill, Ontario.

www.ellinbessner.com